From wild animals confined for exploitation, like millions of Danish mink killed due to coronavirus mutation fears, to their non-caged wild brethren in cities and towns reappearing as human activity decreased due to lockdown restrictions, 2020 offers a stark reminder of just how sensitive many wild animals are to anthropogenic interference. They are close enough to share diseases with us, yet unfamiliar enough that we often perceive their presence as an elusive shadow that only belies alien resilience.

It is useful here to avoid words which obscure individual lives, like ‘wildlife’ and ‘species’ because the terms in which we frame our coexistence with the other, whether animal or not, are constructed, in strong part through language, from folklore to law (Mussawir 2013 pp. 89-91, Bevilacqua 2013 pp. 75-77).

If constant efforts to ‘manage’ wild animals (Minteer and Collins 2005, pp. 1805-1808) and the current biodiversity crisis suggest attitudes and approaches to human impacts on wild animal interests are inadequate, who constructs and governs these relationships, which evidently fail to ensure wholesome coexistence? All social actors, including corporations, non-governmental organisations, and academia play important roles.

This post, however, focuses on two essential political protagonists, the first one because it is widely considered central by other social actors, and the second because it has the potential to greatly improve human attitudes and impacts on wild animal interests:

- public governance institutions, such as national/international government, law, and conventions (henceforth governance), which, by enabling/disabling economic, socio-political, and geographic dynamics at a fundamental level, regulate our coexistence with animals; and

- the public, through political, economic, and social participation. Let us specifically consider the role of communities and democratic engagement at the local level, which is less formal than higher institutions (Rahman et al. 2017, p. 824) while still being capable of playing a significant societal role in improving human impacts on the interests of wild animals.

Why is institutional governance limited in its potential to promote these interests?

Prevailing public discourses suggest we primarily need systemic, governance-led change to improve or minimise human impact on wild animals (Otomo 2013, p. 166). Why should this be challenged?

In practical terms, governance as an instrument for mitigating human impact and promoting wild animal interest is problematic because:

- it can lack flexibility, detail, local expertise, and traction (Otomo 2013 p. 167, Rahman et al. 2017 p. 836). In other words, because governance frameworks must be applicable in diverse environments, their configuration must be formulaic. This is unsatisfactory because, with divergent interests in the balance, any loss of context sensitivity can generate detrimental or unsustainable lowest-common-denominator approaches.

- although institutional interventions related to wild animals’ interests have their place where large-scale coordination is required, even in such cases, human impacts are not always adequately managed through governance efforts. For instance, under 1% of international waters are managed as protected areas (Raynal, Levine, and Comeros-Raynal 2016, p. 302).

In more conceptual terms:

- governance sometimes protects wild animal interests, deliberately or incidentally, but it also acts to kill and exclude. Animals considered desirable (native/emblematic, endangered, exploited/domestic) are sometimes protected by the very processes through which other, typically wild communities are exterminated, often with infliction of agonising pain. Governance of wild animals is thus highly biopolitical—it distributes resources to let/make live and let/make die (Wadiwel 2013, p. 121). Management and protection can only impart imbalanced power relationships over wild animals, as subjects to be governed, without agency or right to non-intervention, unlike sovereign entities (Donaldson and Kymlicka 2011, p. 170). Because it is based on a social contract, governance can only deem intrinsically important the interests of subjects it considers legitimate political agents, which currently excludes wild animals.

- because our institutions have been developing with(in) neoliberalism, and thus conceive economic value as the key societal driving force, they are shaped by the primacy of market dynamics (Eagleton-Pierce 2016, p. 28). The priority of governance is to protect private property and enforce power relations and resource distribution. This includes the commodification of animals (Otomo 2013, p. 166), which demonstrates an intractable conflict of interests: when governance manages human impacts on the lives of wild animals, it systematically prioritises economic interests, because that is its mandate. It is not an instrument in service of the equitable sharing of common goods. It is easier to imagine including wild animals becoming included as stakeholders in a commons-centric governance system than in our neoliberal institutions.

How can community and local democracy initiatives improve human impacts on wild animal interests?

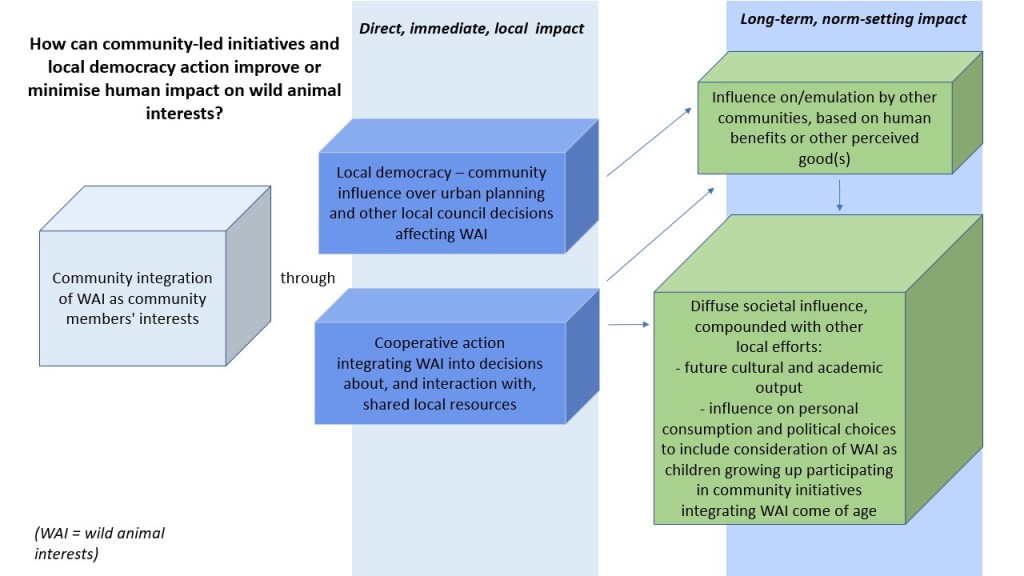

Local/community actions vary depending on their context. The following is one example of a community in which various initiatives have been undertaken to improve or lessen impact on wild animals. It demonstrates the potential for less formal approaches to impact mitigation and wild animal interest promotion to be all at once effective on short timescales, adaptable, and likely to bear self-amplifying fruit over the long term (as this is only a short piece, key aspects of these benefits are summarised in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 – Potential impacts of local initiatives on wild animal interests

As an example, in East Cheshire, England, two types of local projects are being used to support wild animals:

- community initiatives such as the Alsager Urban Wildlife Initiative, Sustainability Group, Wounded Badger Patrol, and Compassion in World Farming local group involve residents in campaigns and actions to support wild animal interests.

- a local councillor has been engaging regularly with the local council, working alongside community groups, and sometimes leading the way to human impact improvements, which has been emulated by other councils/communities.

Community-level projects can reform our relationships to wild animals in profound ways, immediately and on the long term, precisely because they shape values at the community level, which people can experience directly. Children seeing driving speed seasonally restricted to protect wild animals’ life cycles, or a built environment and land management adapted to include wild animal-friendly features, may grow up to deem normal the inclusion of wild animals as members of the community on respectful terms that allow these animals to thrive alongside, or preserved from the reach of, humans. This may also prepare them to understand the plight of less familiar wild animals exposed to human impacts, from wild fish (Hassell, Barret, and Dempster 2020, pp. 487-490) to birds (see e.g. May et al. 2020), badgers or wolves.

Conclusion

For governance to improve human impacts on wild animals and embrace attitudes likely to promote wild animal interests beyond what it can achieve within the scope of efforts that are essentially ancillary to economic pursuits, its mandate would need to be fundamentally reimagined.

Governance can only consider a subject’s interests if it recognises them as a legitimate political agent, whereas community initiatives can directly and agilely improve human impacts on the interests of wild animals, as well as shift societal expectations and norms through diverse local practices.

References

Alsager Town Council (2020). Wildlife corridors [online]. Available at: https://www.alsagertowncouncil.gov.uk/2020/05/wildlife-corridors/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Bevilacqua, C. B. (2013). ‘Chimpanzees in court’ in Otomo, Y. and Mussawir, E. (eds), Law and the Question of the Animal. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 74-88.

Cheshire Wildlife Trust (undated). Badger vaccination [online]. Available at: https://www.cheshirewildlifetrust.org.uk/wildlife/badger-vaccination (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Crewe Chronicle (2018). Alsager is ‘swift friendly’ [online]. Available at: https://www.cheshire-live.co.uk/news/chester-cheshire-news/alsager-is-swift-friendly-15031426 (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Butler, M. (2020). Mink scandal costs Danish minister his job amid botched cull [online]. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-18/danish-minister-ousted-over-mishandling-of-mink-culling-case (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Eagleton-Pierce, M. (2016). Neoliberalism: The Key Concepts. Abingdon, England, UK: Routledge.

Eskander, P. (2017). An analysis of lethal methods of wild animal population control: vertebrates [online]. Available at https://was-research.org/paper/analysis-lethal-methods-wild-animal-population-control-vertebrates/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Hassell, K., Barrett, L. T., and Dempster, T. (2020). ‘Impacts of Human-Induced Pollution on Wild Fish Welfare’ in Kristiansen T., Fernö A., Pavlidis M., van de Vis H. (eds) The Welfare of Fish. Animal Welfare, vol 20. Springer, Cham, pp.487-507. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-41675-1_20 (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Jamieson, D. (1997). Animal liberation is an environmental ethic. Available at: https://acad.carleton.edu/curricular/ENTS/faculty/dale/dale_animal.html#N_14_ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Kretchmer, H. (2020). These locked-down cities are being reclaimed by animals [online]. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid-19-cities-lockdown-animals-goats-boar-monkeys-zoo/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

May, R., Nygård, T., Falkdalen, U., Åström, J., Hamre, Ø., and Stokke, B. (2020). ‘Paint it black: Efficacy of increased wind turbine rotor blade visibility to reduce avian fatalities’. Ecology and Evolution, 10(16), pp. 8927-8935.

Minteer, B. A. and Collins, J. P. (2005). ‘Ecological ethics: building a new tool kit for ecologists and biodiversity managers’. Conservation Biology, 19(6), pp. 1803-1812. DOI: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00281.x (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Mussawir, E. (2013). ‘The jurisprudential meaning of the animal’ in Otomo, Y. and Mussawir, E. (eds), Law and the Question of the Animal. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 89-101.

Otomo, Y. (2013). ‘Species, scarcity and the secular state’ in Otomo, Y. and Mussawir, E. (eds), Law and the Question of the Animal. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 166-174.

Rahman, H. M. T., Saint Ville, A. S., Song, A. M., Po, J. Y. T., Berthet, E., Brammer, J. R., Brunet, N. D., Jayaprakash, L. G., Lowitt, K. N., Rastogi, A., Reed, G., and Hickey, G. M. (2017). ‘A framework for analyzing institutional gaps in natural resource governance’. International Journal of the Commons, 11(2), pp. 823-853. DOI: 10.18352/ijc.758 (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Raynal, J., Levine, A., and Comeros-Raynal, M. (2016). ‘American Samoa’s Marine Protected Area system: institutions, governance, and scale’. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy, 19(4), pp. 301-316.

Schweig, S. T. (2017). Volunteers are saving wounded badgers in the UK [online]. Available at https://www.thedodo.com/in-the-wild/wounded-badger-patrol-helps-animals-england (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Smith, J. (2018). Memorial for Lost Species, Milton Park, Alsager [online]. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/LostSpeciesSpaceAlsager/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Stibbe, A. (2001). ‘Language, power and the social construction of animals’. Society & Animals, 9(2), pp. 145-161, DOI: 10.1163/156853001753639251 (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

UN (2019). UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’ [online]. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

Wadiwel, D. (2013). ‘Whipping to win’ in Otomo, Y. and Mussawir, E. (eds), Law and the Question of the Animal. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 116-132.