Like human welfare, animal welfare is complex. As a subject of interest, it was a ‘social construct’ before it also branched out into science (7). Nowadays, of course, animal welfare science is a key aspect of both debates on the treatment of animals and practical management of animals in industries that exploit them.

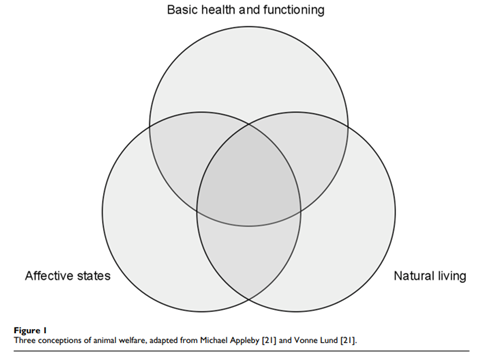

Animal welfare as it is now construed is therefore a multi-faceted subject. A conciliatory description might state that it ‘includes health, emotional state, and comfort while moving and resting, and is affected by possibilities to show behavior and relationships’ with peers and humans (3). This can be measured using objectively quantifiable indicators. But those are influenced by the values of the humans designing them (6), who often have different views on what welfare means – see Fig. 1 (Fraser 2008) below.

I often wonder whether it is possible for animals to be exploited, i.e. live lives on terms dictated by what is profitable, and also enjoy a life without suffering due to their exploitation, a life in which the norm is the experience of positive states.

In this post, I’d like to invite you to reflect with me on what welfare means. We’re going to do this by getting to know farmed goats, and what welfare means for them.

Why goats?, you ask.

The welfare of farmed goats deserves attention because:

- it’s often forgotten. For instance, the influential EU Welfare Quality® project long excluded goats (4, 8). On the demand side, consumers of goat-derived products (1) show a marked focus on the traditional value of eating goats, and on purchase price, rather than demonstrating significant concern for the animals’ welfare. This can to some extent be contrasted with the situation in pig, chicken and cattle consumption, where consumer concern with basic welfare provisions have led to some efforts on the part of producers.

Goats are mostly farmed extensively (1), especially in the developing world, where it is their unparalleled hardiness that make them more desirable to exploit than more fragile species. When most people think of extensive farming, they picture low population densities and a life led rather like in nature, tranquil and wholesome. Most people might not realise that extensively-farmed goats can suffer from access to suitable and sufficient food, water, shelter and care, parasites, predation, and of course premature death and exploitation if these two issues are considered welfare issues – premature death primarily because it denies opportunities to experience positive states later in life and exploitation because it restricts some natural behaviour. What’s more, extensive farming systems are often under less scrutiny than intensive ones (1, 2); - some goats are also kept in the hell of intensive farming, especially in industrialised countries like the UK, which is even less conducive to good welfare. Intensive goat farming is increasingly considered an attractive option in developing countries like India and Pakistan as well. There’s therefore some reason to worry that increasing numbers of goats will, in the near future, be subjected to intensive farming, especially with significant human population rising in developing countries, since goat products form a key part of local diets in many areas, including arid and semi-arid areas, which may become more widespread as climate change and other ecological issues progress, making goats even more of a popular species to exploit.

What is it like to be a goat?

- goats are sociable (14), with a sophisticated social order – they even mediate conflicts between one another (5)

- for the first weeks, the doe-kid bond is crucial. For instance, maternal grooming and other social interaction help build kids’ microbiome, which influences chemical signals affecting neural activity and behaviour (5)

- they’re capable of complex social learning, such as precise eating sequences of specific plant for nutritional and even medicinal (e.g. anti-parasite) purposes, through mothers’ teachings and mutual observation – these traditions can even be considered to form a culture (5)

- goats understand human cues (19). They learn from and communicate with us (16). They recognise individual humans, prefer happy faces and seem to process emotional information like us – the right brain hemisphere mainly processing negative emotions and the left, positive ones (18)

- being adaptable (14) and intelligent (5), goats love challenges, even without rewards attached, so cognitive/sensory enrichment benefits their welfare (10).

So, what might farmed goats need to enjoy good welfare?

Let’s start with a mention of obviously negative aspects of farming on goat welfare. Then we’ll consider what to take into account to assess welfare based on goats’ perception and behavioural and physiological needs, and how positive aspects of welfare might be taken into account.

Pain and injury

- Like other farmed species, goats are often subjected to painful invasive procedures such as castration, marking for identification and dehorning. The impact of these procedures isn’t limited to pain at the time of the procedure: some can lead to chronic pain and, by increasing the animal’s stress level long after the procedure itself, depress their immune system, making them more vulnerable to illness.

- Housing design, especially but not exclusively in confined systems, can cause pain and injury, for instance lameness (i.e. mobility problems) due to unsuitable or poorly maintained flooring.

These are obvious welfare issues caused by inadequate environment and physical management. Indeed, because these are fairly easy points to assess, most farmed-animal welfare indicators are ‘resource-based’, e.g. handling/environmental factors of illness, injury, abnormal behaviour (4).

I’m now going to focus on less obvious challenges involved when determining whether farmed goats are experiencing, or can experience, good welfare conditions. I’m putting a bit of emphasis on positive welfare, which considers animals’ ability to enjoy the experience of living, because like many, I think welfare is more than merely the absence of suffering. While positive welfare is thus an important part of the bigger picture in assessing welfare, it is harder to assess than obvious signs of illness or injury.

Including positive welfare criteria into assessments: too many unknowns

Farmed animal welfare policy is increasingly focusing on ensuring animals enjoy a ‘life worth living’, or ideally a ‘good life’. To this end, the recent EU AWIN Project (for ‘Animal Welfare Indicators’) sought to include more animal-based welfare indicators into on-farm monitoring, which could be a good way to focus more on ensuring the animals assessed do experience some positive states, as much as their dystopian environment and forced handling can allow. But such indicators must be reliable, valid, and easy to use during short monitoring sessions (4). When it comes to goats, these are hard requirements to meet, since:

- extensive goat farms rarely feature health monitoring programmes and intensive systems simply don’t allow goats to fully express natural behaviour, which by definition compromises their positive welfare. Besides, behavioural indicators are difficult to observe in crowded conditions; and

- we know little about what positive welfare means for goats. For instance, we don’t really understand object manipulation, vocalizations, behaviour indicating frustration, facial/body expressions (17) and so on. In order to carry out analyses based on qualitative behaviour assessment, which effectively considers what animals’ attitude suggest about their psychological state (8), we would need to be able to interpret their behaviour much more finely.

Below are some examples of both current knowledge limitations and poor application of what we do know about goat welfare in day-to-day farming practices. Here’s a question to bear in mind as you read this section: can we hope to reconcile the requirements of profitable exploitation with goats’ needs at all?

Inadequate capacity to meet nutrition-related needs

- Because goats rely on nutritional balance to avoid pathogens and to balance their microbiome, competing over limited/inadequate food sources can cause illness and distress (5).

- Goats have evolved to eat high up off the ground, so they’re sensitive to parasites from food given at ground level (8). The argument whereby confinement offers good protection against parasites (6) is thus questionable, especially since stressful and often unhygienic conditions in which animals live in intensive systems tend to promote the growth and spreads of parasites and other pathogens. In this sense, anti-parasite treatments barely compensate the damage done, rather than provide an advantage compared to life in goats’ natural environments.

- Along with maternal/social influence, goats have personal feeding preferences, partly based on morphology/physiology, but this is environment-specific and thus difficult to study.

- In intensive conditions, goats are often only fed two concentrated fodder meals per day, whereas their metabolism thrives on lengthy, frequent eating sessions. Low-ranking goats may suffer due to competition and we know concentrated feed leads to abnormal behaviour in kids (8). As in other farmed species, feeding concentrated formulas is often accompanied by an inadequate supply of fibre in the diet, which, based on what we know about other species, may also be a factor contributing to health and behaviour issues (20).

Inherent conflict between confinement and behavioural needs

- Goats’ social inclination towards humans (5) and positive judgment bias (17) are frustrated in automated, crowded intensive farms, where they get little positive human interaction compared to traditional smallholdings. Even heart development is affected by lack of positive human interaction (14).

- Their intra-species social needs – communication, spatial organisation, behaviour synchronisation (17), mating behaviours, mother/baby bond, social learning and the like – are also frustrated in confined environments (8). These environments are designed to maximise profit rather than to provide a suitable layout for goats based on their needs and preferences. Precisely because they are designed to minimise costs, these facilities are also crowded to high densities.

- Frequent isolation (14) and separation/re-grouping cause stress and conflicts (3, 9).

- Early weaning, which is the norm on dairy farms (14), compromises kids’ lifelong prospects by causing failure to learn eating behaviours, frail physical development, and abnormal behaviour.

- Preference testing helps assess positive welfare, but findings are not necessarily applied. Goats prefer different flooring materials for different activities, and, ideally, avoid eliminating waste on surfaces that expose them to pathogenic residue (11). But due to cost/practicality priorities, many farms don’t provide suitable, and suitably diverse, floorings, restricting goats’ well-being and protection from pathogens.

- Horns are crucial in social behaviour (12, 13), so dehorning deprives goats of the opportunity to express natural behaviours. Unfortunately, dehorning is often the first or only method chosen to prevent injuries due to the stress and high population density demanded by intensive farming systems, as it is easier than investing in a less dreadful environment for the animals to live in.

Prospects

Positive welfare could technically be enhanced by designing exploitation conditions based on:

- preference testing;

- animal-based welfare indicators such as vigour and time spent on/postures adopted in certain behaviours (17);

- implications of goat/human interaction and communication (16), like using cues to understand needs;

- pro-social behaviour and emotional contagion (15), i.e. mood change based on the state one animal observes in another; and

- cognitive/physical enrichment (14, 16).

However, welfare improvement options are often not implemented by animal exploitation systems. Equally importantly, they only answer some of the most basic ethical problems caused by goat farming (16). These avenues for amelioration still permit, perhaps even encourage, exploitation, by keeping the animals just healthy enough for their bodies, milk or offspring to be saleable.

When included in farm assurance scheme commitments, knowledge about animal welfare lulls consumers into thinking that animals enjoy a relatively painless, perhaps even good life. A life better than no life at all – which in many cases is at best debatable, since animal welfare is always subordinate to the demands of profitability, and typically not aligned with the latter.

Help these intelligent, sensitive animals live fulfilling, dignified lives by going vegan and supporting animal advocacy organisations.

References

1. Sullivan, R., Amos, N. and van de Weerd, H., 2017. Corporate reporting on farm animal welfare. An evaluation of global food companies’ discourse and disclosures on farm animal welfare. Animals, 7(12), 17.

2. Rodríguez-Serrano, T., Panea, B. and Alcalde, M., 2016. A European vision for the small ruminant sector. Promotion of meat consumption campaigns. Small Ruminant Research, 142, 3-5.

3. Tarazona, A., Ceballos, M. and Broom, D., 2019. Human relationships with domestic and other animals. One health, one welfare, one biology. Animals, 10(1), 43.

4. Caroprese, M., Napolitano, F., Mattiello, S., Fthenakis, G., Ribó, O. and Sevi, A., 2016. On-farm welfare monitoring of small ruminants. Small Ruminant Research, 135, 20-25.

5. Landau, S. and Provenza, F., 2020. Of browse, goats, and men. Contribution to the debate on animal traditions and cultures. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 232, 105127.

6. Fraser, D., 2008. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 50(S1).

7. Fraser, D., 2003. Assessing animal welfare at the farm and group level: the interplay of science and values. Animal Welfare, 12(4), 433-443.

8. Battini, M., Barbieri, S., Vieira, A., Can, E., Stilwell, G. and Mattiello, S., 2018. The use of qualitative behaviour assessment for the on-farm welfare assessment of dairy goats. Animals, 8(7), 123.

9. Patt, A., Gygax, L., Wechsler, B., Hillmann, E., Palme, R. and Keil, N., 2013. Behavioural and physiological reactions of goats confronted with an unfamiliar group either when alone or with two peers. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 146(1-4), 56-65.

10. Meyer, S., Puppe, B. and Langbein, J., 2010. Cognitive enrichment in zoo and farm animals – implications for animal behaviour and welfare. Berliner und Münchener tierärztliche Wochenschrift, (123), 4-54.

11. Sutherland, M., Lowe, G., Watson, T., Ross, C., Rapp, D. and Zobel, G., 2017. Dairy goats prefer to use different flooring types to perform different behaviours. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 197, 24-31.

12. Shackleton, D. and Shank, C., 1984. A review of the social behavior of feral and wild sheep and goats. Journal of Animal Science, 58(2), 500-509.

13. Barroso, F., Alados, C. and Boza, J., 2000. Social hierarchy in the domestic goat: effect on food habits and production. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 69(1), 35-53.

14. Miranda-de la Lama, G. and Mattiello, S., 2010. The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Ruminant Research, 90(1-3), 1-10.

15. Düpjan, S., Krause, A., Moscovice, L. and Nawroth, C., 2020. Emotional contagion and its implications for animal welfare. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, 15(046).

16. Nawroth, C., Langbein, J., Coulon, M., Gabor, V., Oesterwind, S., Benz-Schwarzburg, J. and von Borell, E., 2019. Farm animal cognition – Linking behavior, welfare and ethics. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 6.

17. Mattiello, S., Battini, M., De Rosa, G., Napolitano, F. and Dwyer, C., 2019. How can we assess positive welfare in ruminants?. Animals, 9(10), 758.

18. Nawroth, C., Albuquerque, N., Savalli, C., Single, M. and McElligott, A., 2018. Goats prefer positive human emotional facial expressions. Royal Society Open Science, 5(8), 180491.

19. Nawroth, C. and McElligott, A., 2017. Human head orientation and eye visibility as indicators of attention for goats (Capra hircus). PeerJ, 5, e3073.

20. Cronin, G.M., Rault, J.–L. and Glatz, P.C. 2014. Lessons learned from past experience with intensive livestock management systems. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 33 (1), 139-151.